EXPOSED AFTER DECADES

The US Navy took every precaution possible to avoid being accused of espionage. The Soviet cables were not cut or damaged; the wiretapping was done by induction, taking advantage of a then-controversial US law that made it illegal to pick up signals escaping from communications equipment. Of course, everyone involved knew that in practice the tactic lacked even the slightest legal basis.

For days, the device continued to listen to conversations that passed through the copper wire. Some of it was of strategic value: maintenance schedules, patrol areas, the departures and arrivals of this or that submarine. But other information was just family gossip or the longing comments of a sailor eager to get home. The device’s useful life was as short as its battery. But the important thing was that it had proven its ability to spy with impunity on a secret line of communication.

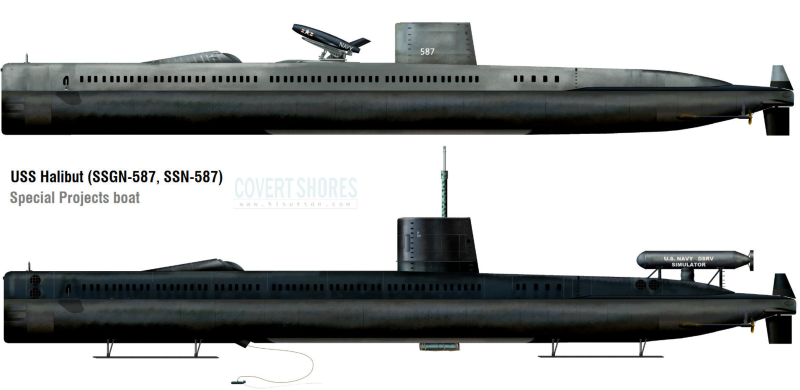

Just before the Halibut was scheduled to depart, a massive storm erupted in the Sea of Okhotsk. Waves 6 to 8 meters high swept across the ocean, causing the submarine to rock and sway, held only by two anchors on the bottom. Finally, as if to add drama to an action movie, both anchor cables snapped and the Halibut floated freely to the surface, despite the best efforts of the crew.

The divers were outside at the time, being pulled along by their own diving tubes and lifelines to the submarine. If they rose too high, the sudden loss of pressure could be fatal, so the commander ordered the ballast tanks flooded. Halibut suddenly sank, landing violently on the bottom. This was an unsafe situation because sand could block the reactor’s cooling water pipes.

The ship remained on the seabed until the storm subsided. It then performed a complex maneuver that involved emptying its ballast tanks to surface urgently, and immediately re-flooding them so that the ship would not emerge above the surface and risk detection.

After that storm, the Halibut did not return to base. It also tried to collect the fragments of the anti-ship missiles that the Soviets were testing in those waters; thousands of pieces, some only a few centimeters long. Unfortunately, they only collected metal fragments, warheads, and electronic altimeters, but not a trace of the infrared homing device. It was later discovered that the Russian missiles did not use such guidance systems.

The USS Halibut’s mission capability was so great that the US Navy’s intelligence department commissioned Bell Laboratories to build another, much more sophisticated eavesdropping device.

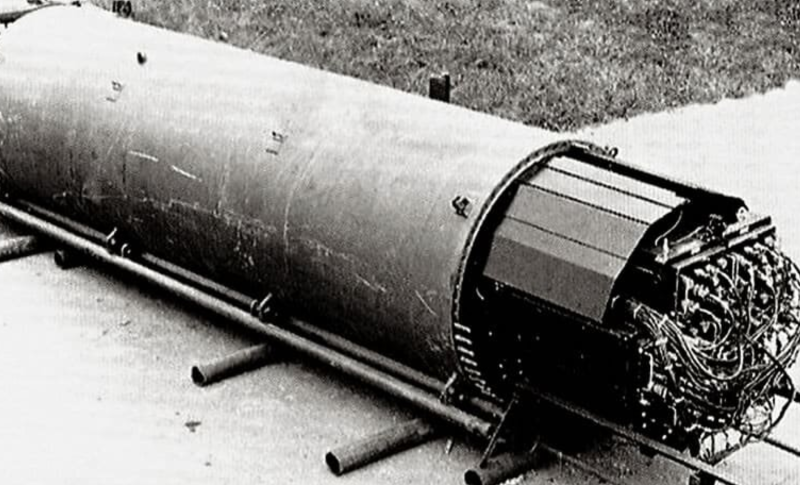

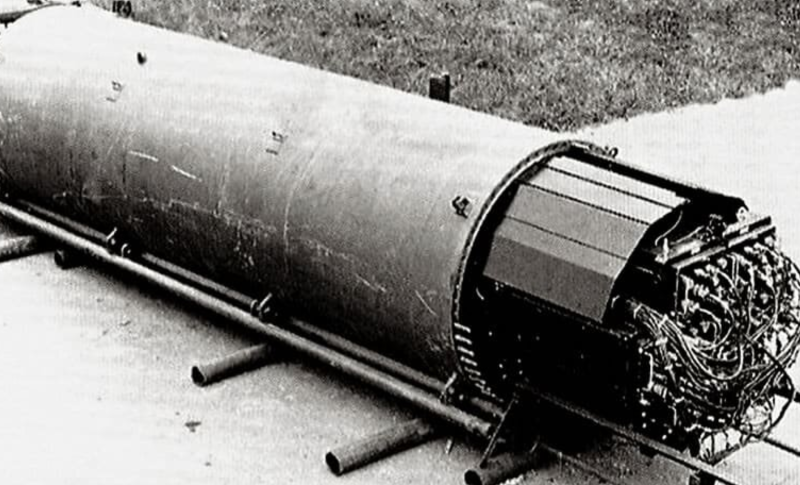

The result was a cylindrical device, 3 meters long and 1 meter in diameter, filled with electronics capable of identifying conversations taking place on both lines. The data would be recorded on magnetic tape (the individual tape reels were 1 meter in diameter) and, crucially, a small plutonium nuclear reactor would be used to power it. Teams of divers would periodically “visit” the listening device to collect recordings and, if necessary, make repairs.

Halibut returned to the Sea of Okhotsk twice more, in 1974 and 1975. On those occasions, it was fitted with skis on its bottom that allowed it to sink gently to the bottom. It was also fitted with explosives to destroy the hull, in case it was discovered.

Other submarines replaced the Halibut for nearly 10 years. In 1981, American surveillance satellites detected a group of Soviet ships equipped with cranes and other rescue systems directly above the device’s location. Another submarine, the USS Parche, was sent to retrieve it before the entire listening system was discovered, but it arrived too late. The Russians had already removed it and shipped it to Moscow.

After being analyzed, the device became a Russian war trophy. For years, it was displayed at the Moscow Museum of the Armed Forces, along with the remains of the U-2 piloted by Gary Powers—another famous incident in the history of espionage—and the remains of a Tomahawk missile. A sticker attached to the inside of the listening device read “Property of the United States Government.”

But how could the Russians find it?

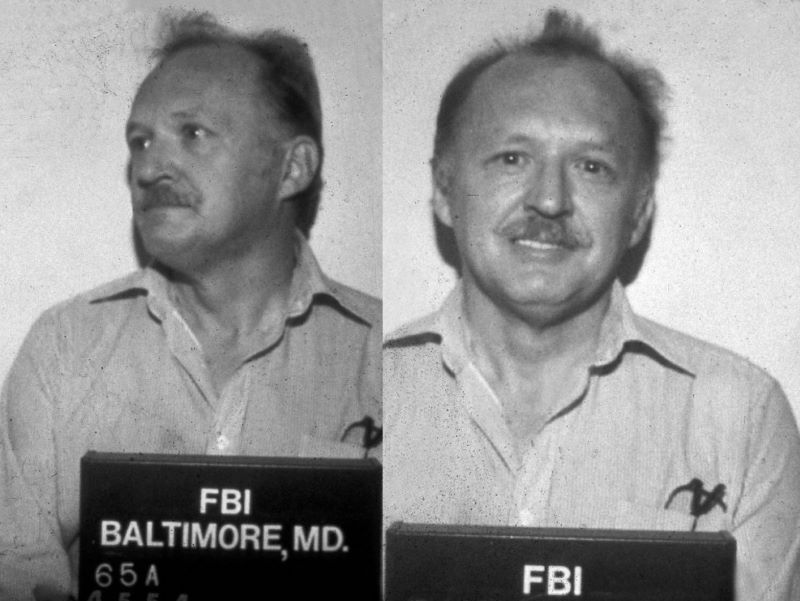

As in spy movies, it was the job of a spy, a former employee of the US National Security Agency (NSA) to be exact. His name was Ronald Pelton, he was in financial trouble and saw no better solution to his problem than selling classified information to Moscow. Pelton had no documents to offer, but he had a good memory of where the wiretapping system was installed. In return, he received $35,000.

Pelton was captured and sentenced to three life sentences, but was eventually released after serving 30 years and died a few years ago. Captain Bradley, the mastermind of the mission, died in 2002 without any public recognition for his exploits. Halibut’s commander, Jack McNish, died in 2015. By that time, his submarine had been decommissioned and scrapped.

Operation Ivy Bells was not a one-time intercept of foreign intelligence, but a continuous operation with multiple Soviet underwater military channels, 24 hours a day, for decades. The information gathered from this operation is said to have helped the Americans in negotiating the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) and other treaties, and many even believe it helped end the Cold War.