Starmer himself has robotically warned the upcoming Budget on Oct 30 will be “painful”, adding – in stark contrast to the sunny 1997 vibe – that “things will get worse before they get better”.

The Institute of Directors’ (IoD’s) business optimism index fell sharply in August, with the Government’s talk of tax hikes and increased regulation “denting confidence in the UK business environment”. The IoD reported investment intentions for the year ahead dropping at their fastest rate since the start of the Covid pandemic lockdowns.

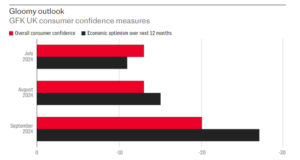

GfK’s long-running measure of consumer confidence plunged by seven points to -20 in September, we learned last week, down from -13 the month before, with households now more anxious about their finances and the broader economy. The public is also suddenly feeling far less upbeat about the economic situation a year from now, with that confidence measure dropping 12 points to -27.

Despite relatively stable inflation and the prospect of further interest cuts – the Bank of England held its base borrowing cost at 5pc last week, having lowered it from 5.25pc in August – the economic outlook is gloomy. Following the partial withdrawal of winter fuel payments, and clear signs taxes are going up, companies and households are nervously awaiting Labour’s Budget.

Government borrowing increased to £13.7bn last month, up £3.3bn on the previous month and the third-highest August gap ever between state spending and taxation. Total national debt has soared 4.3 percentage points over the last year, we learned last week, topping 100pc of GDP – so the overall debt pile now equals the annual value of everything produced in the economy.

With the public finances so weak, Labour’s first budget is set to be focussed on revenue-raising measures, not crowd-pleasing give-aways. What a contrast to Labour under Tony Blair, who came into office with the national debt at just 36pc of GDP, providing ample scope for the government to borrow and spend more.

Most significantly of all, the UK economy grew no less than 4.9pc in 1997 – and at an average rate of 3.4pc over the rest of Blair’s first term, leading to another convincing election win in 2001.

Steady growth leads to higher living standards, spreading a feel-good factor. It means higher tax revenues even at constant tax rates, facilitating more government largesse, while the national debt burden still falls as a share of a bigger GDP. That in turn keeps the bond markets happy, so the state can borrow more cheaply.

Yet UK GDP flatlined in both June and July, with the economy set to grow by barely 1pc during 2024 as a whole and the outlook sluggish for several years to come. Labour desperately needs the economy to kick into gear, not only to avoid a fiscal crisis but to reverse Starmer’s plunging approval ratings and ensure this isn’t a one-term Government.

With the best will in the world, though, I fail to see how any of Labour’s plans, at least those announced so far, will spark growth. Labour has emphasised the need for planning reform to boost house building and other much-needed infrastructure projects – and I couldn’t agree more.

But the Party’s plans to railroad applications through, against the wishes of local communities, will result in endless legal challenges. So too will proposals to obtain agricultural land for building using extensive compulsory purchase orders.

Labour’s “job-boosting green energy revolution” also won’t boost growth any time soon – on the contrary. Moves to close down much of the UK’s oil and gas industry have openly alarmed trade unions – mindful the sector provides 250,000 well-paid jobs.

Proposals to restore the ban on sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 meanwhile risk handing much of the UK’s car market to Chinese manufacturers, which are way ahead when it comes to electric vehicles. That threatens the million or so jobs across our automotive production industry.

The best way to foster growth is to lower the tax burden from today’s 70-year high while introducing more commercially-savvy regulation across a range of sectors. Labour is about to do the opposite.

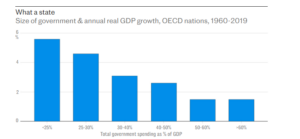

In his new book, Return to Growth, the businessman Jon Moynihan presents OECD data over the last 50 years to demonstrate that “small state” economies – those where taxation and government spending are relatively low as a share of GDP – have tended to grow much faster than their competitors.

GFK, IMF, “Return to Growth”

Yet Labour is now pushing a “pro-growth” narrative in the context of an already sky-high tax burden that’s about to go up even more.

Tony Blair said earlier this month that when he took office the mood in the country was “pretty optimistic… but the zeitgeist today is different, more anxious”.

That mood is coming from the top.

Starmer’s party secured just 33pc of votes cast back in July, on a very low 60pc turnout. So just 20pc of the electorate backed Labour, which means four out of five didn’t. Party managers are mindful that unless growth and living standards improve soon then the public mood, already downbeat, could turn decidedly nasty.

Labour desperately needs growth to kick into gear – the public mood is about to turn nasty

Three months on from Tony’s Blair’s 1997 landslide, the national mood was decidedly upbeat. New Labour had secured 13.5m votes, on a historically high 73pc turnout – the electorate not only calling time on 18 years of Tory rule but actively backing a young and charismatic prime minister.

Along with Oasis, Puff Daddy and Will Smith, D:Ream’s annoyingly catchy chart-topper – Things Can Only Get Better, adopted as Blair’s election campaign theme tune – was dominating the airwaves. Public optimism was high.

The situation today, almost three months into Keir Starmer’s Government, could hardly be more different. Business and consumer confidence are in a nosedive, amid concerns Labour’s leadership is talking Britain into a downturn.

Starmer himself has robotically warned the upcoming Budget on Oct 30 will be “painful”, adding – in stark contrast to the sunny 1997 vibe – that “things will get worse before they get better”.

The Institute of Directors’ (IoD’s) business optimism index fell sharply in August, with the Government’s talk of tax hikes and increased regulation “denting confidence in the UK business environment”. The IoD reported investment intentions for the year ahead dropping at their fastest rate since the start of the Covid pandemic lockdowns.

GfK’s long-running measure of consumer confidence plunged by seven points to -20 in September, we learned last week, down from -13 the month before, with households now more anxious about their finances and the broader economy. The public is also suddenly feeling far less upbeat about the economic situation a year from now, with that confidence measure dropping 12 points to -27.

Despite relatively stable inflation and the prospect of further interest cuts – the Bank of England held its base borrowing cost at 5pc last week, having lowered it from 5.25pc in August – the economic outlook is gloomy. Following the partial withdrawal of winter fuel payments, and clear signs taxes are going up, companies and households are nervously awaiting Labour’s Budget.

Government borrowing increased to £13.7bn last month, up £3.3bn on the previous month and the third-highest August gap ever between state spending and taxation. Total national debt has soared 4.3 percentage points over the last year, we learned last week, topping 100pc of GDP – so the overall debt pile now equals the annual value of everything produced in the economy.

With the public finances so weak, Labour’s first budget is set to be focussed on revenue-raising measures, not crowd-pleasing give-aways. What a contrast to Labour under Tony Blair, who came into office with the national debt at just 36pc of GDP, providing ample scope for the government to borrow and spend more.

Most significantly of all, the UK economy grew no less than 4.9pc in 1997 – and at an average rate of 3.4pc over the rest of Blair’s first term, leading to another convincing election win in 2001.

Steady growth leads to higher living standards, spreading a feel-good factor. It means higher tax revenues even at constant tax rates, facilitating more government largesse, while the national debt burden still falls as a share of a bigger GDP. That in turn keeps the bond markets happy, so the state can borrow more cheaply.

Yet UK GDP flatlined in both June and July, with the economy set to grow by barely 1pc during 2024 as a whole and the outlook sluggish for several years to come. Labour desperately needs the economy to kick into gear, not only to avoid a fiscal crisis but to reverse Starmer’s plunging approval ratings and ensure this isn’t a one-term Government.

With the best will in the world, though, I fail to see how any of Labour’s plans, at least those announced so far, will spark growth. Labour has emphasised the need for planning reform to boost house building and other much-needed infrastructure projects – and I couldn’t agree more.

But the Party’s plans to railroad applications through, against the wishes of local communities, will result in endless legal challenges. So too will proposals to obtain agricultural land for building using extensive compulsory purchase orders.

Labour’s “job-boosting green energy revolution” also won’t boost growth any time soon – on the contrary. Moves to close down much of the UK’s oil and gas industry have openly alarmed trade unions – mindful the sector provides 250,000 well-paid jobs.

Proposals to restore the ban on sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 meanwhile risk handing much of the UK’s car market to Chinese manufacturers, which are way ahead when it comes to electric vehicles. That threatens the million or so jobs across our automotive production industry.

The best way to foster growth is to lower the tax burden from today’s 70-year high while introducing more commercially-savvy regulation across a range of sectors. Labour is about to do the opposite.

In his new book, Return to Growth, the businessman Jon Moynihan presents OECD data over the last 50 years to demonstrate that “small state” economies – those where taxation and government spending are relatively low as a share of GDP – have tended to grow much faster than their competitors.

GFK, IMF, “Return to Growth”

Yet Labour is now pushing a “pro-growth” narrative in the context of an already sky-high tax burden that’s about to go up even more.

Tony Blair said earlier this month that when he took office the mood in the country was “pretty optimistic… but the zeitgeist today is different, more anxious”.

That mood is coming from the top.

Starmer’s party secured just 33pc of votes cast back in July, on a very low 60pc turnout. So just 20pc of the electorate backed Labour, which means four out of five didn’t. Party managers are mindful that unless growth and living standards improve soon then the public mood, already downbeat, could turn decidedly nasty.